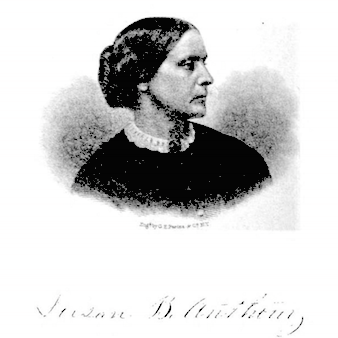

Learn all about Susan B. Anthony, the Women's Rights and Civil Rights Activist.

Introduction

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) was a prominent women’s rights and civil rights activist. She was the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1892 through 1900 and a major founder of women’s suffrage groups. While most famous for her efforts to end slavery and establish women’s right to vote, she advocated for everything from the temperance movement and labor rights to girls’ education. Throughout her life, she sought to achieve equal rights for all.

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) was a prominent women’s rights and civil rights activist. She was the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1892 through 1900 and a major founder of women’s suffrage groups. While most famous for her efforts to end slavery and establish women’s right to vote, she advocated for everything from the temperance movement and labor rights to girls’ education. Throughout her life, she sought to achieve equal rights for all.

Early Life

Susan Brownell Anthony was born in 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts, in the U.S.A. As a young woman, her family used their farm in New York state for regular gatherings of abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, who became a lifelong friend. Abolitionists were people who spoke out against slavery, and many Quakers (including Anthony and her family) were part of this this movement. Anthony was also active in the temperance movement, which agitated against the use of alcohol.

Anthony was a teacher and school principal, but she was so involved in the abolitionist and temperance movements that in 1849 she quit teaching to become a full-time activist.

This would lead her, in 1852, to advocate for women’s rights–especially woman suffrage (the right to vote). This was where she would gain widespread recognition.

Advocacy and Women’s Rights

Many social issues were interwoven in the mid-19th century. It was common to see an activist in one area deciding to lead a battle cry in a completely different arena.

This was clearly seen in Anthony–a woman who was indignant at being kept from addressing temperance rallies because she was a woman. In a stroke of serendipity, Anthony met the activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton at an abolitionist meeting in 1851. The two activists had been blocked at many a turn because of their gender, and realized the only way they could get a proper voice would be to force their way into politics.

In the 1800s, American politics was a world inhabited only by men. Women weren’t even allowed to vote, which was the issue that Anthony and Stanton decided to make a stand on. After the Woman’s New York State Temperance Society was established in 1852, they turned their sights solidly on women’s rights. They petitioned for women’s suffrage and for the right of married women to own property and to keep the wages they earned, and the two activists founded the New York State Woman’s Rights Committee.

Through the 1850s, Anthony was an advocate for teachers, championing the idea that males and females had the exact same capability to learn and that they should have equal rights both to be taught and to teach. She also argued that all races should have equal opportunities for education and became active in the American Anti-Slavery Society through the late 1850s and early 1860s. She both spoke out and circulated written pamphlets, enduring taunts and even violence.

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, Anthony returned to women’s rights. She and Stanton were among those who founded the Women’s National Loyal League (1863), the American Equal Rights Association (1866), and the National Woman Suffrage Association (1869). These groups wanted everyone to have equal rights–women and men, black people and white people–and called for voting to be open for all. A running slogan at the time was: “Men their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

Anthony and Stanton were very active via the press, knowing that this was a clear way to get their message out. In 1868 they started a weekly newspaper called The Revolution. The Revolution advocated equality, decrying both racial animosity and gender inequalities. In addition, she called for support for labor unions, in order to achieve reduced working hours, improved working conditions, and better wages; Anthony founded the Workingwomen’s Central Association in 1870.

The year 1869 saw a schism within the women’s rights movement. While the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) took a state-level approach, focusing on winning women the right to vote one state at a time, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), founded by Anthony and Stanton, wanted to pass a Constitutional amendment, establishing women’s right to vote nationwide all at once. Eventually, in 1890, the AWSA and NWSA coalesced into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Anthony refused to ever back down. As she wrote and spoke about women’s suffrage around the country, she also took many personal risks–organizing strikes, making herself heard no matter the controversy, and even defying the law by voting in the 1872 election (which resulted in her arrest and conviction, and a fine).

End of Her Life

Age hardly slowed Anthony down. When she was 80, in 1900, she successfully pressed to get women admitted as students to the University of Rochester. In 1905 she even lobbied for women’s suffrage to President Theodore Roosevelt. Tragically, she would die the next year, having never seen equal rights or women’s suffrage in her lifetime.

Legacy

In was only in 1920 that American women gained the right to vote nationwide, with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; NAWSA was the organization behind this achievement. Susan B. Anthony’s legacy extends far beyond this. Her passion for equal rights can still be felt in the current shrinking of the gender gap in society, in the waves of modern feminism, and even in her tiny likeness on U.S. one-dollar coins.

Related Pages

Read about women who changed the world—explorers, inventors, artists, women’s rights activists, and more.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a prominent 19th-century women’s rights proponent and anti-slavery crusader.

The orator and writer Frederick Douglass was an abolitionist, a person who fought against slavery. He was the first African-American citizen appointed to a high rank in the U.S. government