Read all about Native American totem poles here! Many worksheets and activities are also available.

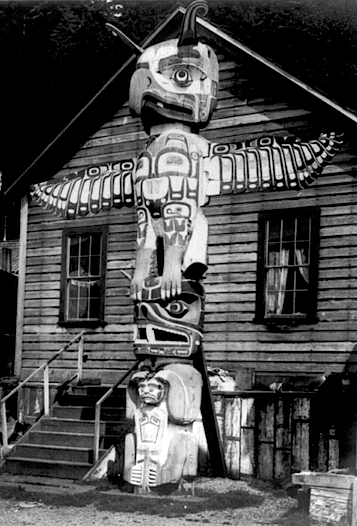

‘Namgis totem pole in British Columbia, Canada.

The eagle is the father’s family crest, and the grizzly bear is the mother’s family crest.

Introduction

Totem poles are huge wooden columns which were made by Native Americans along the Pacific coast of North America (in the Pacific Northwest, from what are now Oregon and Washington, and stretching up through modern-day Canada and Alaska). Traditionally, each totem pole tells the story of a Native American family’s ancestral spirits and family history, pictured in human and animal form.

The spirits are shown as people, mythical beasts, and treasured wildlife—often the bald eagle, grizzly bear, moose, beaver, otter, mountain goat, wolf, whale, porpoise, seal, sea lion, or salmon.

Which Tribes Made Totem Poles?

Though totem poles are now a common symbol of Native American culture, only some tribes actually produced them, including the Haida, the Tlingit, and the Coast Salish tribes. Only those who lived in areas with trees which were at least dozens of feet tall even had the opportunity.

Totemism and Animal Carvings

These large art pieces have come to represent an important facet of Native American culture. This isn’t too surprising, as many of the tall structures still exist and capture peoples’ imaginations. The portrayal of traditional legends can even be seen in the name. The word “totem” comes from the Okibwa tribe’s “totemism”—the belief that sacred or supernatural animals were the forebears of humans. This is why depictions of animals were carved into totem poles: the Native Americans were telling a story as well as paying homage to their ancestry.

Materials

Totem poles were made from red cedar timber. Cedar is common in the Pacific Northwest and is sturdy enough to withstand wind, rain, and time. The colors were vibrant, and of course all came from natural sources, making them rare and costly in time to produce.

Memorials, Stories, and Legends

The structures can be found both indoors and outdoors, with some of the largest ones set up outside in remembrance of departed chiefs or of a family’s line of ancestors. Others commemorated wars, love, or great events, or even ranted against a rival! But many of them told the history and legends of the tribe. Interestingly, while each carved image in the pole tells part of the story, the symbols usually weren’t in any specific order.

Value to Historians

One reason why totem poles are crucial to understanding Native American history is that little written early history of these tribes exists. Instead, historians and archaeologists rely on oral history (stories passed on from generation to generation) and studying objects that have been preserved. Totem poles are incredibly important in this because they show the tribes’ legends!

It’s hard to determine how long totem poles have been made, but the carving and the ceremonies that accompanied them, including grand feasts with much dancing and mask-wearing, have been around since at least the 1700s. Unfortunately, with the swell of European settlers and a lack of conservation, a great number of totem poles have been destroyed. There are still many, but most of these are now housed in museums. A few tribes have returned to making totem poles to preserve their culture, but not at all to the extent that they used to.

More on Native Americans

Totem poles are huge wooden columns which were made by Native Americans along the Pacific coast of North America. Traditionally, each totem pole tells the story of a Native American family’s ancestral spirits and family history, pictured in human and animal form.

Native Americans lived in many different types of housing. Read about tipis, grass houses, wattle-and-daub houses, pueblos, wigwams, longhouses, plank houses, and even igloos!

A printable worksheet on Pocahontas (1595?-1617), with a short biography, a picture to color, and questions to answer.

Answers: 1. Chief Powhatan, 2. John Smith, 3. Jamestown, 4. John Rolfe, 5. England.

Chief Pontiac (1720-1769) was a great leader of the Ottawa Indian tribe. He organized his and other tribes in the Great Lakes area to fight the British, in what is known as Pontiac’s War.

Sacajawea or Sacagawea (1788-1812) was a Shoshone Indian giude, interpreter, and negotiator for Lewis and Clark on their exploratory expedition to the U.S. West. She traveled with them from North Dakota to the Oregon coast and back.

Read about Sitting Bull (1831-1890), the courageous Lakota leader. He was the last Native American chief to surrender to the U.S. government.

Fill in the blanks in this printout, which is a short biography of the Native American leader Sitting Bull. He was the last chief to surrender to the U.S. government.

Word bank: battle, Canada, expansion, father, South Dakota, Stand, courageously, government, surrender, Custer, reservations, warrior.

Read about Crazy Horse or Tashunka Witko (1849?-1877), a Lakota Sioux warrior who was a leader in the Native American victory over the U.S. government in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Custer’s Last Stand.

Fill in the blanks in this short biography of the Native American warrior Crazy Horse, who was victorious over Gen. Custer in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Word bank: American, army, Bighorn, born, brave, Custer, photographs, reservations, sculpture, South Dakota, surrender, westward.

These printable graphic organizer worksheets can be used to organize material for reports on Native Americans. Includes each of: Canada/Alaska, the U.S., North America, Central America, and South America. Each region has a simple graphic organizer and a more complex graphic organizer.

Find words relating to Native Americans in this wordsearch puzzle. Look up, down, left, right, and diagonally! The PDF file includes both the word-search puzzle and the answer key.

Word bank: Sitting Bull, Powhatan, Sacajawea, Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, Ottawa, Lakota, Ghost Dance, Pontiac, Tribes, Sioux, Pocahontas, Chief, Little Bighorn

Make a tepee, a totem pole, a Kachina doll, a rattle, a dream catcher, and a paper canoe! Or combine a number of these simple crafts on a Native American bulletin board for a visually exciting display.